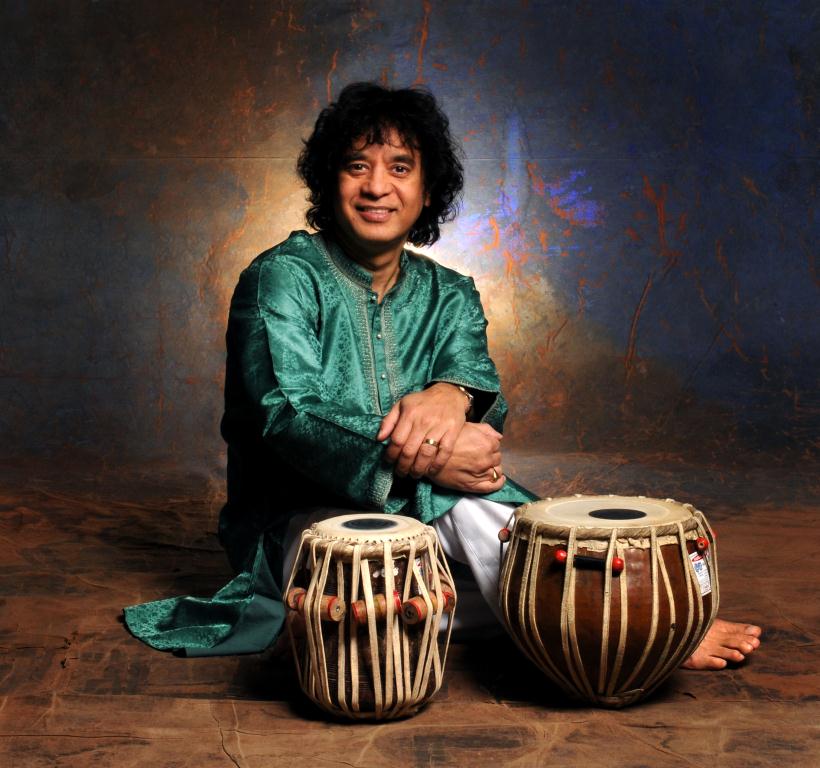

It’s almost 5 p.m. Having just completed an interview with one of the TV channels, Zakir Hussain steps out of the room. Moments earlier the lady publicist has haughtily warned us – me and my friend Rajendra – not to bother him much as he is too tired after a taxing schedule. Taxing schedule no doubt – an overnight, long distance flight, a busy press conference in the morning, a hurried Thai lunch in the afternoon and then that TV interview. The man must be dead tired and I don’t blame him if he just wishes to be left alone. I have almost relinquished all hopes of a meaningful chat, just waiting to say the final good-bye. The handsome Tabla maestro smilingly walks straight up to me and asks disarmingly, “Where shall we sit?” and all my doubts about a potential disaster of an interview turn to delight in a flash.

Cool, confident and courteous to the core, Zakir bowls you over instantly. He is a real charmer answering questions with aplomb and authority. Under that casual carefree exterior, he has one thing that is missing from many a stalwart’s resume – Charisma. He is charismatic and he knows it. Time and again our conversation is broken by overenthusiastic intrusions of his admirers, each of whom is received as graciously and he comes back to the flow of conversation without missing a beat. You don’t become a master of rhythms by missing beats. Do you?

I set the ball rolling by telling him that I am interviewing him for Young Times – a youth mag and that he is considered a symbol of youth and glamour in Indian music. “Oh, come on. I am already fifty now.” He tries to wave off the compliment but can’t. I can see he is flattered. I begin my questions.

Q. Was the decision to become a percussionist your own or was it a forced one?

A. “ It was entirely a personal choice. In fact my mother opposed it as far as she could. All mothers want their kids to become doctors or engineers. But for me, my father, the late Ustad Allarkha, was and still is my inspiration. Since he was a master exponent of tabla, I wanted to emulate him in every way and I started playing the instrument since the age of three. He never pressurized me. He would always tell me that the pupil must inspire the teacher. So only when pupil has it in him, teacher can make something great out of him. But somehow he always sensed that I had it in me.

He used to train separately in an adjacent room so to seek his attention I would deliberately make mistakes while playing tabla. Hearing the wrong note, he would shout across aloud and I would then ‘correct’ the mistake. Then he realized that I was doing it to attract his attention and started training with me. By the age of seven, I was performing on stage along with him. I still cherish those moments.”

Q. How do you compare the musical scene in your father’s era with the present one?

A. “That era of late forties and early fifties, the music had just come out of the durbars and palaces. Musicians who were earlier retained by Maharajas as their personal entertainers had suddenly lost their support after Independence and to survive they had to perform for commoners. But even then the audiences were a select few having the dough. Most of them were connoisseurs no doubt but still the medium was much more confined to some chosen ones. The musical tastes were very conservative.

Nowadays the audiences are much wider and also much wiser. Today they are aware of musical trends all over the world. Classical, Jazz, Reggae, Rock, Techno- they are comfortable with all kinds of music. They are much more appreciative of changes in new direction and of course, the media coverage has also played a big role.”

Q. In the past vocalists dominated the musical scene and instrumentalists were secondary. But then the picture changed and now instrumentalists are stars in their own right. What do you feel about this change?

A. “Obviously as an instrumentalist I welcome this change in attitude but I still feel that vocal medium is more powerful than the instrumental medium. The words, the expressions, the emotions all play their part in a vocalist’s performance whereas instrumentalist has only the notes to go with. Only a connoisseur can understand the nuances of instrumental performance but even a common listener can relate to a tappa, thumri, kajri or dadra sung by a good singer. Voice will always have that edge. Pt.Bhimsen Joshi’s ‘Sant waani’ or Shobha Gurtu’s Jhoola are experiences in themselves and are much more popular than instrumental albums.”

Q. Were you a teenage rebel against the tradition?

A. “No, actually as a teenager I was quite a meek student following in my Guru’s, my father’s footsteps. I wanted his approval, his appreciation all the time so there was no question of being a rebel against tradition.

That kind of thing started much later when I got older, started moving around the world and experimenting with other forms of musical expression. I could see that my father had by then entrenched himself completely into traditional music and for him it was difficult to change. But I was a youngster who had grown up listening to Elvis and had no rigid views on influence of outside music. At the same time I was old enough not to fear losing my own Indian musical identity. So I experimented. You can say I became a rebel with a cause.

My cause was to find a universal musical expression. When you go to a different country with a different culture, you must learn their language, their customs to make them understand- who you really are. That provided for me the stimulus for fusion.”

Q. How do you see the influence of Hindi film music on the overall musical sensitivity of Indian audiences?

A. “Classical music is an intimate art form that requires a closed chamber environment and a musically literate audience. Film music is much easily accessible and everyone understands it. I admire the earlier era of film music when composers like Madanmohan made such nice use of Indian classical music in their tunes. Those songs certainly helped classical music in the long run as audiences could connect a particular raag to a particular song. So Raag Hansdhwani was associated with Jaa tose nahi bolun Kanhaiya

and Tu jahan jahan chalega defined Raag Nand.

Recently people like Pt.Hariprasad Chourasiya and Pt.Shivkumar Sharma have shown that even classical artists can do well in film music.”

Q. Did you face in opposition from the traditionalists as regards your radical musical views and experiments?

A. “Well, the answer is yes. But I feel they were justified in opposing. Their view is – ‘Look, we have created something great and timeless. Please don’t disturb and distort that.’ At the same time, every new generation comes up with new views and new vision. Improvisation is a continuous process. So in that way artists like me were justified in taking a new path. Maybe tomorrow I might not like some young upstart going in a new direction but that is bound to happen. Every new generation tries to improvise things and take them a bit further and then turns to another corner.”

Q. What essentially is the difference between Indian and Western music?

A. “All over the world there are the same seven basic notes – twelve if you also calculate the minor ones. Indian music is based on holding a single note at a time whereas simultaneous multiple notes is the norm in western music. In Indian music we have additional well-defined 22 microtones to differentiate raags and that provide a much greater scope for subtlety and variation.”

Q. Pt.Ravishankar, L.Shankar, yourself – why there are so few Indian icons on the world music scene?

A. “In an army there is a single general and 3-4 commanders. People know those top people but that doesn’t mean the army is useless. It is same here. There was a time when the western world equated Indian music with one name- Pt.Ravishankar. But over the years situation has changed dramatically. More and more Indian music artists are being appreciated over the globe. There is not a single moment when Indian music is not being performed somewhere in this world and it is classical music –not film music. I think no other music – be it English, Japanese, Chinese or Arabic – can claim this unique distinction.”

Q. What do you feel about being the ‘Glamour boy’ of Indian music?

A. “To tell you jokingly, every dog has his day and I am having mine. Actually I feel the audiences always need a figure with whom they can identify, they can connect. Earlier artists like Pt.Onkarnath Thakur, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan or Pt.Ravishankar fitted the bill. Maybe today I am able to fill the breach. Tomorrow someone else will come.”

Again that disarming, charming smile appears on his face and he politely asks to be excused. We stretch our luck by asking him to pose with us for photographs. He obliges immediately. No histrionics, no hurry – a perfect gentleman. Then he bids us adieu. A memorable interview comes to an end.