In early 1981 while still new to the Emirates and flitting between locum jobs I received a call from the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Deira. A polite voice asked if I would be free to call upon Mr. Ravi Shankar, who wished to consult for a skin problem. Surely a joke, I thought, then being relatively inexperienced professionally and all of 26 years of age. I thought it was probably a prank call arranged by some friend who was aware of my musical interests.

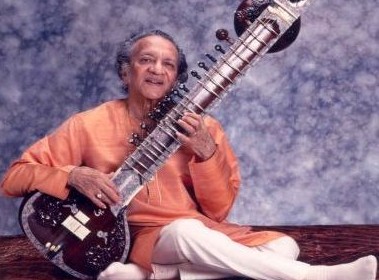

It wasn’t, and as I arrived in the lobby I was met and escorted up by an aide who was carrying the maestro’s freshly pressed silk kurta. I was dazed by the utter simplicity of Panditji, who had already travelled the world and achieved world fame – in short, had ‘been there, done that’ even before the phrase was coined. Conversation was limited to relevant details of the consultation but he did mention George Harrison briefly, and I left with a complimentary pass to the evening’s concert. Even as the curtain dropped at the end, panditji with seasoned practice skilfully evaded fans and reporters and had vanished to his room.

Much later, in the 1990s, he was due for another concert in Dubai, and two ladies from our little circle of music aficionados were breathless with excitement: they had been chosen to play the tanpura (a stringed drone instrument) on stage! They had more to tell after a preliminary briefing session with Ravi Shankar – sari and backdrop colours were to be (or not be) of a specific colour, and seating positions were to be strictly complied with. We wondered if the star was becoming crotchety with age, but, as writer R.K. Narayan reveals in his memoir My Dateless Diary, Ravi had these and other rules firmly established as early as 1958 while performing at New York’s Rockefeller Center.

The day after the concert I managed to gain an audience once again, this time as a freelance writer. Panditji had a feeble recollection of our earlier meeting but was now eager to talk about music. Not being well versed with the nuances of Indian classical music, I played it safe by asking him only about his work in films. Aside from Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy and English films like Gandhi and Charly, his involvement in mainstream Hindi cinema had been restricted to a mere handful of movies like Neecha Nagar, Anuradha and Godaan.

For a world famous musician his reaction at not being recognized as a film composer was remarkably one of regret. “I was spontaneous and innovative”, he said. “I never believed in written scores, I just went to the recording studio, taught the singer the song and told the musicians what to play. For an Asha Bhosle song in Godaan I had multiple sitars playing in harmony, something unheard of in Indian music. I could have done so much for cinema but they never gave me that opportunity”.

I asked why he let it bother him. After all, there were dozens of his LPs in circulation, as a solo artiste, and in collaboration with other musicians both Indian and western. His reply was insightful: “A film song is seen by millions of people and remains in the mind of each viewer. Every time he hears the song the memory of the film is reinforced and the song then becomes a part of his growing years. Compositions from that era have now transcended the movies themselves and have become ageless. On the other hand a recording of a live stage programme has no staying power beyond its innate musical value, except perhaps in the nostalgia it inspires in the minds of the few that witnessed it”. (It reminded me of Julie Andrews telling a British TV presenter how much she regretted being passed up on the chance to do My Fair Lady’s Eliza Doolittle on screen after playing the character for years on the Broadway stage. “My performance will live in the memory of theatre-goers who saw me, and then too only as long as they live. A film role is forever”.)

Ravi Shankar was always clear and firm in his demands with his promoters and organizers – a full list of requirements would need to be met such as flight bookings, hotel rooms and limos, all as specified. Yet he could be disarming and gracious with fans. One Dubai-based sitar player who nervously rang from the lobby was immediately invited up to his room. Ravi asked him many questions about his progress, his guru (whom he knew of) and then invited him to play his (Ravi’s) own sitar for a bit, offering some corrections and advice, but only up to a point (“You have a guru and I must not intrude on his style”).

Now the legend has once again slipped away from the public after the curtain has fallen on life’s grand concert.

*(The author is a Dubai-based dermatologist and a music aficionado.)